The shoulder is a shallow ball-and-socket joint, which provides an exceptional range of movement but also makes it inherently unstable. The socket (glenoid) is made deeper by a rim of fibrocartilage known as the labrum. Additional stability comes from thickenings of the joint capsule (ligaments) and the rotator cuff muscles. Shoulder stability relies on these ligaments remaining intact and the muscles being strong. A shoulder dislocation occurs when the ball (humerus) comes out of the socket (glenoid). This can be partial (subluxation) or complete (dislocation). After the first dislocation, the labrum and ligaments are often torn, increasing the risk of recurrent instability, especially in patients under 30 years old.

There are two main types of shoulder instability:

The primary causes of shoulder dislocation and recurrent instability include:

The symptoms of shoulder dislocation and recurrent instability can vary but typically include:

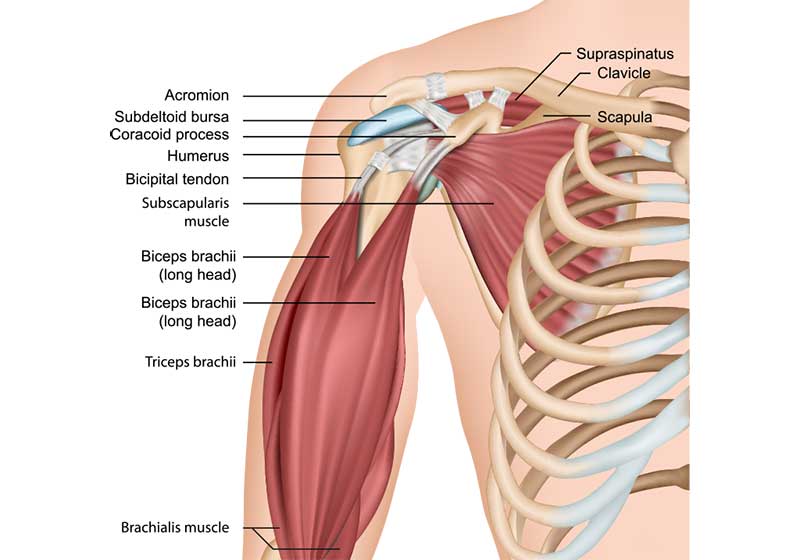

The shoulder joint comprises several key structures that contribute to its function and stability. The glenoid, part of the scapula (shoulder blade), forms the socket, while the humeral head forms the ball. The labrum, a rim of fibrocartilage, deepens the socket and provides a suction effect, enhancing stability. Ligaments, which are thickenings of the joint capsule, connect the bones and restrict excessive movement, thus preventing dislocation. The rotator cuff muscles surround the shoulder joint, aiding in movement and stabilising the joint by keeping the humeral head centred in the socket during motion.

In shoulder dislocation, these structures are compromised. The humeral head is forcibly displaced from the glenoid, often tearing the labrum and overstretching or tearing the ligaments. This damage diminishes the shoulder’s stability, making it more susceptible to future dislocations and recurrent instability.

Non-surgical treatments are often the first line of defence for shoulder dislocation and recurrent instability, especially in cases of atraumatic instability. Physiotherapy plays a central role in strengthening the muscles around the shoulder, particularly the rotator cuff and scapula stabilisers. A physiotherapist will design a tailored exercise program to improve muscle balance, enhance joint stability, and restore normal shoulder function. Specific exercises may include resistance training, range-of-motion exercises, and proprioceptive drills to improve shoulder control and stability.

Activity modification is another important aspect of non-surgical management. Patients are advised to avoid activities that provoke symptoms or put the shoulder at risk of dislocation. This might include modifying sports techniques or avoiding certain overhead movements. Additionally, wearing a shoulder brace during high-risk activities can provide extra support and help prevent dislocation.

Pain management is also essential. Over-the-counter pain relievers and anti-inflammatory medications can help alleviate pain and reduce inflammation. Ice packs applied to the shoulder can provide additional relief, especially immediately following an injury. In some cases, corticosteroid injections may be considered to reduce inflammation and pain, although these are generally reserved for severe symptoms that do not respond to other treatments.

When non-surgical measures are insufficient to prevent recurrent shoulder instability, surgical intervention may be necessary.

One of the most effective surgical treatments for traumatic shoulder dislocation is repairing the torn labrum and ligaments. This procedure is most commonly performed using keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery.

In an arthroscopic repair, a small camera (arthroscope) and specialised instruments are inserted through tiny incisions to access the shoulder joint. The torn labrum is reattached to the edge of the socket (glenoid) using suture anchors, and the ligaments are tightened. This procedure restores the stability of the shoulder joint.

Recovery typically involves staying in hospital for one night and wearing a sling for six weeks. Most patients can drive a car after six to eight weeks, and return to sports is usually possible at around six months.

In cases of atraumatic shoulder instability, where the shoulder dislocates with minimal effort and there is typically no labral tear, physiotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. Surgical intervention is less common for atraumatic instability unless conservative treatments fail to provide stability.

These notes from OrthoSport Victoria are for educational purposes only and are not to be used as medical advice. Please seek the advice of your specific surgeon or other health care provider with any questions regarding medical conditions and treatment.

If you are looking to book an appointment, please call us on